Website planning is often a complex process. Sitemaps are website structures used to plan, structure and strategize the content organization of your website.

The aim of the site mapping process is to allow an easier planning of the website’s structure. Planning a website’s architecture also offers a unique opportunity to incorporate user search intent, which is often not capitalised on.

The following resource will offer insight on organising a website’s architecture in a way that considers users and the intent, with which they are visiting the site. This approach also provides more context for crawlers to better understand your site, too. A win-win situation for everyone involved, really.

It’s important to note that the following article will make some assumptions and discuss the most common of cases, leaving out industry- and case-specific considerations that apply for niche websites and discuss concepts using a generalist approach.

Background

Since 1993, searching behaviours are defined in academic literature by four different things:

- the goal of the search interaction;

- the method of interaction;

- the mode of retrieval; and

- the type of resource interacted with during search.

While originally developed for library searches, scientists analyzing queries in digital searches realised all four descriptors apply to digitals searches, too. While the method of interaction and mode are the same.

The users of search engines still enter a query, results are retrieved, results are analysed, viewed or refined as deemed needed by the user in the hypermedia environment. The goals and type of resources shown are what really defines search intent.

Information and the sites that host it are accessible to users everywhere at their fingertips. This leads to a variety of different people with different degrees of previous knowledge on a given topic searching for information on a wide array of topics, displayed in different formats. Modern day search results are, thus, driven by context, ubiquity, scale and variety.

The classification we, as SEOs, use was first developed in 2002, originally containing only navigational, informational, and transactional search intent, thus focusing on the type of content the user wants or expects to see.

Users with informational search intent query the web indicating an intent to locate a particular topic or information snippet, which can help them address or satisfy an informational need they are struggling with.

Users with navigational search intent demonstrate a desire to be taken to the homepage of an institution or organisation they are already brand-aware of.

Users with a transactional search intent demonstrate a desire to obtain something other than the information, typically performing a web-mediated transaction.

These are the top three levels of search intent. However, they can be subdivided into categories, adding an additional two states – commercial and localised search intent.

Users with commercial search intent demonstrate a desire to perform a comparative evaluation of the merit of select institutions or organisations they are already aware of (in the process of which they might also be exposed or introduced to similar institutions in the same niche that can satisfy their transactional intent).

Users with localised search intent indicate the desire to complete a transaction or an effort to find a solution to a recognised need that is close in physical and geographical proximity to the user.

According to two resources by Ahrefs and Getstat, the search intent behaviour of a user corresponds to their placement on the marketing funnel, i.e. the user journey to purchase. To put it differently – the conversion likelihood of the user increases with their movement down the search intent funnel, correspondingly to the conversion marketing funnel.

Past research suggests that approximately 75% of queries can be classified into a single category of user intent (i.e. informational, navigational, or transactional) with a high degree of certainty. I’ve previously discussed how these intents can be used for keyword and query classification as part of the keyword research process using turn-key solutions such as Data Studio. Let’s now discuss how to apply the concept of search intent to website structure planning.

Here are the three things to consider when planning a website’s structure for search intent:

- Optimizing the site’s main pages, based on the type of search intent they serve

- Understanding the internal links needed to assist moving users from one search intent to another, without having to go back and perform an additional search (i.e. organising the site, based on the user journey)

- Being aware of the additional factors that can contribute to the site’s performance and the methods and tools you can use to identify pitfalls in the architecture

1. Optimize the site’s main pages, based on the type of intent they serve

Oftentimes I hear clients stating that their website goals are increasing organic traffic and leads or conversions. Of course, they want to help their clients continue choosing them for business every day at the same time, too. In many cases what they fail to realise is that these three aims serve different search intent, or specifically – the three main categories of search intent, discussed in the previous section.

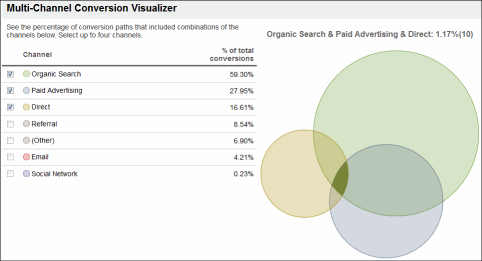

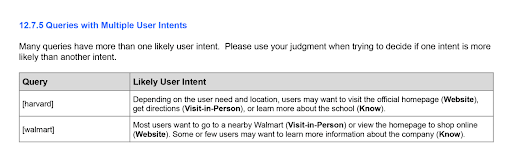

This means creating three clusters of pages that are optimised for different search intent. Data from scientific studies indicates that 25% of queries can be attributed to more than one search intent. Google has also discussed this in their guidelines.

Considering this, paired with the different characteristics that define web searches and user expectations, some pages can serve a blended search intent, too.

Let’s go through the different pages that exist on a website, their aim and the search intent they should be serving.

Category 1: Resource Pages (Informational Search)

We are all painfully aware of the importance of addressing the three pillars of SEO and good search performance – content, tech and links. Well, resource pages are what makes up a big percent of the content performance.

Resource pages serve for the most part a singular aim – to increase organic traffic via serving an informational search intent. Other CRO tactics can be implemented on such pages to increase the conversion rate, as well as r content strategies can be implemented in the content to increase the brand building effect of the pages. The primary aim of them will remain the same, though.

Typically such pages are kept in a separate subdirectory, or even sometimes a separate subdomain, which used to be called a blog but that trend is now slowly exiting the scene. Nowadays, the blog section can be called anything but that, with examples, depending on the industry including ‘a magazine’, ‘a content resource center’, or ‘a learning hub’.

There are different types of pages that can be included in this group, yet they all share one thing in common, the biggest intent they serve is informational. With a caveat, though! A portion of the different page types in this group fall into the category of those 25% mentioned above, which serve more than one search intent.

For instance, if we were to look at a blog post in the form of a listicle, the main intent that it will serve will be informational, yet if one of the items on the list is the brand itself, then this piece of content is also serving commercial search intent, as well as has a brand-building effect.

For another example, a white paper’s aim might be to demonstrate the superiority of doing something the way that is being done by the company in question, or perhaps to assert thought leadership in a given topic. Here, while informational search intent is still dominant, there are also distinguishable elements of the content that satisfy commercial and transactional search intent. To elaborate, sections that show superiority in comparison to the market and/or other competitors, or an introduction of a pioneering new method of doing things, such as a new tool or service.

Category 2: Company Pages (Navigational Search)

Another category of pages are the company pages.

Such pages include, but are not limited to

- Company Values, Aims, and Philosophy pages

- Careers Page

- Our Culture Page

- About us / Our Approach

- People / Team Page

- Author / Contributor Pages

- Homepage

- Request a quote / Contact Form

Company pages are typically considered by site owners as pages that assist with employer branding. When used appropriately, the main aim of the company pages is to satisfy navigational searches for people already aware of the brand or business, seeking additional information in conjunction with the brand name. However, such pages have a secondary goal, which has recently been highlighted by Google’s EAT (Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trust) update.

This goal is to establish the credibility of the business, as well as its team members or contributors as experts in the field, with which it can signal to search engines that the quality of information provided in other parts of the website (such as the resource pages) is good.

Category 3: Product Pages (Transactional Search)

Product pages are all pages that relate to the transactional aims of the business. These can be product listings, solution pages, features deep-dives, tech specifications, pricing pages, etc.

Such pages have a very low informational intent, and a very high transactional intent. Depending on the business’ strategy, there can be a commercial search intent incorporated, e.g. ‘us vs the competition’ competitor comparison landing pages.

These pages will typically be paired with searches that indicate readiness to buy. The search terms will typically be highly competitive, high value keywords, especially if short-tail and they will typically receive a high number of sponsored links.

Search engines usually have a way of categorising these searches from other non-transactional searches and adjusting the results accordingly. For instance, research indicates that for informational queries, search engines could concentrate on presenting results that are not stores and that do not provide transactional services as their main goal. Thus, non-transactional queries receive fewer sponsored links as a result.

If there is one thing that SEOs and PPCs are both painfully aware of, it’s that transactional searches are highly competitive and (as a result) – costly for the business.

Here is where the importance of building a website architecture that serves the search intent user journey organically comes in, or otherwise – creating a website that enables a high number of organic visits via high-quality resource-type content and moves users from informational to transactional search intent all without encouraging them to return back to perform additional searches.

[Case Study] Refine your SEO strategy based on relevant data and granular segmentation

2.Use internal links for creating a search-intent-driven user journey

So, you’ve built an amazing page for each of your sections. You’ve used keywords that are relevant to the search intent in the particular topics. Your pages are optimised technically and the content is both user- and search-friendly. What now?

After creating search intent-optimised pages, let’s now discuss how to structure them in a way that is coherent for the user journey.

This is where internal linking comes in.

According to Bernard Huang, Google gives scoring not only the traditional factors such as technical, backlinks and content, but also your ability to keep users on the site, instead of sending them back to search.

Besides Google’s large database of user queries, they also have information about the sequence, in which these queries occur. This enables algorithmic testing, via tools, such as RankBrain, regarding which content is best to be displayed for a particular search.

So, imagine which website is going to be placed on a higher position in the search index – the one that addresses only one query, or one that addresses the query, and then guides the user to resources that address the additional (subsequent) queries they might have, based on their search intent.

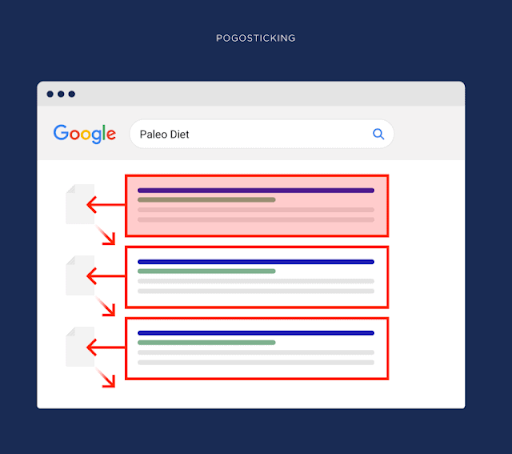

Internal linking is important in the sense that it prevents visitors from ‘pogosticking’ or otherwise – going back to Google with their additional questions and it prevents Google from having to re-rank the million websites it has again, based on the new input. So, internal linking really has the potential to save resources from both a user and a search engine / crawler standpoint.

Source : Backlinko.com

From my experience, there are three internal linking strategies that can be used to assist the user journey:

- Simple matching – linking on a keyword-level to pages that target this keyword

- Topic relevance and content clustering – linking to pages that address a given topic, such as category or pillar pages, whenever a concept that falls within this topic is mentioned in another article

- Search intent enrichment – linking pages on a similar topic that address different parts of the user journey

Search intent enrichment is what I like to refer to the practice of guiding the user from one search intent to the other. For instance, from problem-aware, to solution-aware, to brand-aware, and finally to purchase-ready, all without them having to leave the website.

Let’s explore this via an example in the ecommerce space:

- A user lands on an informational blog post after typing a query in the search console

- In the “Continue reading” (or “Related Articles”) section below the article, there are several choices

- Knowledge enhancement – same search object, different topic, no change in behaviour (information-seeking)

- Intent enrichment – what to do next, same search object, same topic, change in behaviour (from information-seeking to solution-aware)

- This strategy is replicated across other posts in the resource section

- Once the user’s information seek is fulfilled (subject to a good page experience), they might be propelled to shift their search behaviour towards a solution

So if the user has typed initially “how often should I eat beetroot” and landed on an information article titled something along the lines of “benefits of eating beetroot”, then the next logical step in their behaviour is (first) finding out how to cook beetroot, hence another informational recipe, but with a shift towards commercial behaviour and (second) where to buy beetroot and other ingredients from, which has shifted the intent once again to transactional intent.

The aim of the website structure is to facilitate these shifts to the highest extent, without burdening them with having to go through a search once again. Or otherwise – to guide the user from one search intent to the next closest one down the funnel in a seamless, smooth, and organic manner.

What about navigational searches? How to incorporate these pages into the internal linking structure, based on the common visitor’s search intent?

Navigational searches typically have a lower search volume – these are the type of people that are already aware of the problem and the companies or brands that can resolve it, but not yet ready to make a purchase. In the classic user journey theory, this stage is referred to as option consideration, which is characterized by intense information gathering and comparative evaluation. Thus, these users will likely perform additional assisting searches to find information (either on the site’s website, or on in search.)

From a search engine standpoint, research shows that for navigational queries search engines could focus on presenting results that provided links straight to a requested web page, a person’s webpage, or to related web sites.

For instance, a common navigational query is the brand name, such as ‘walmart’, ‘pretty little thing’, or ‘amazon’. For a query like this, the search engine might provide links to the relevant brand’s ecommerce platforms, but it could also provide links to other major retailers in the searchers geographical location (using IP look-ups).

Other research in the field of search intent has highlighted that some users that submit informational queries sometimes expect a certain website among the results. In other words, these queries have an informational intent and with an element of a navigational expectation.

What does this mean from a site owner’s perspective? If a user has submitted an informational query with an expectation about their navigational intent being satisfied, but this intent is not satisfied by the results itself, there is an opportunity for the site to satisfy this intent.

How? By incorporating internal linking from informational content (i.e. resource pages) to navigational content (i.e. company pages), depending on the context.

To provide some examples, this might look like having an author page for each contributor to the blog or other resource sections on the site. Another way would be to provide links in case studies via side box pop-ups to dedicated pages that discuss the team behind a project, which is responsible for the results achieved. Additionally, for white papers, there can also be links to the culture, values, and philosophy pages in the introduction, establishing how the company’s internal environment has become a catalyst for the research presented.

Let’s summarise the approach using a few examples.

Provide links to facilitate the move from informational to navigational search intent and commercial search intent.

By typing a query “how to handle negative comments on social media” the user landed on a page from a social media marketing agency that addressed this topic.

The resource provides links to company pages to establish credibility of the author (link to author page) as an expert in the field, as well as to establish the context about why the resource exists on the site (e.g. “In the agency X (link to about us page) we work with influencers, brands, etc, having to do this on a regular basis”)

The resource provides a CTA-based link to another resource that fulfills both informational search intent further by also enhancing commercial intent – a thought-leadership resource, such as a developed tool, a case study, or a white paper).

Provide links to facilitate the move from commercial to transactional and localised search intent.

When opening the thought leadership resource the user was recommended, the resource contains affirmation via competitive analysis, social validation, and other comparative evaluation techniques that satisfy the user’s commercial search intent, establishing the authority of the brand and author as a subject matter expert in the niche of social media marketing.

The resource provides different pathways, based on the user’s persona:

- Sharing the resource or subscribing to the newsletter (informational search intent)

- Viewing a different resource on the same topic (link to the content cluster page on social media marketing) or a exploring another topic (link to the resource landing page) (informational search intent)

- Getting in touch with the brand if they are a social media influencer or brand interested in collaboration (link to the services page or the contact page/ form) (transactional search intent)

- Learning more about the company culture and getting to know the team, applying for a job as a social media marketing manager (navigational search intent)

Provide links to facilitate the move from commercial and navigational intent to transactional and localised search intent

Wherever relevant on company pages and product pages, mentions are made that satisfy the localisation search intent:

- Links from the product pages to places where the products are available near the user (if such are available)

- Links on the company pages about events near the user (if such are available)

3.Be aware of additional factors, contributing to performance, and the approach you can use to identify pitfalls in the architecture

Of course, in reality the user journey is much more complex and rarely as straightforward, however this is where data comes in to assist you to create an analysis of how the users of your particular website, or even in your industry and niche behave, using a variety of available data touchpoints.

Start by ensuring that your site’s technical SEO hugene is good. While often overlooked, technical SEO factors can seriously destroy the site’s ability to rank in the top positions, especially when basic hygiene factors, such as page experience, indexability, and security are not addressed.

Define the goals of the website and ensure that the architecture aligns with these goals. We mentioned a few throughout this article, but for instance it can be:

- Getting organic visitors via search

- Improving site conversions – e.g. product sign-ups, product purchases, newsletter sign-ups, quote requests, form completions, etc. (depending on the business goals and niche)

- Improving Assisted conversions – ensuring the site acts successfully as part of the omni-channel user journey

By defining the goals of the website, you will have a clearer idea where to focus the content development efforts, especially considering the page categorisation discussed above and the internal linking structure.

Ensure the content on the pages is relevant to the user’s search intent, as well as optimised from an SEO standpoint. There are a variety of tools that use the knowledge graph concept, also used by Google, to help you improve your content (Clearscope and Surfer SEO, to name a few). Classification techniques for keyword search intent, implemented in the keyword research stage, can help you determine the feasibility of certain topics for your niche.

Identify and prune pages and content on the website that fails to generate organic visits by using engagement signals, such as clicks, average time on page, and bounce rate. This can enable you to ensure that you develop topical authority and subject matter authority organically, without it being hindered by poor performing content.

Ensure that the content you produce addresses search intent, as well as the user’s content experience in this topic by taking into account user personas. Through understanding top, middle and bottom of funnel user personas, you can implement techniques and content clusters that address different parts of the purchasing journey.

The sales funnel includes three groups of users:

- top of the funnel (ToFu) – seeking informational content, as they are in their awareness and information-seeking stages of the customer journey

- middle of the funnel (MoFu) – looking for a solution to an already recognized problem or clearly defined need

- bottom of the funnel (BoFu)highly qualified and ready to make a purchase, searching with a high degree of intent.

By implementing techniques such as mega menus, you assist MoFu and BoFu users navigate to the content they are looking for, quicker. Mega menus are expandable menus that display many choices in a two-dimensional dropdown layout. They accommodate a large number of options or for revealing lower-level site pages at a glance.

Another way of catering to user personas, is by matching the search intent with the content experience a user with this profile might expect. This means not only pairing the keywords and queries into intent buckets but also addressing the type of content that the user will expect to see when performing the set query.

To elaborate, if we were to go back to the previous example about beetroot shopping, a recipe page with a video might perform better than one without, as a user at this stage of the user journey might benefit from seeing this content. Similarly, a page about where or how to buy beetroot might benefit from links to ecommerce stores or an embedded map of nearby farmers’ markets.

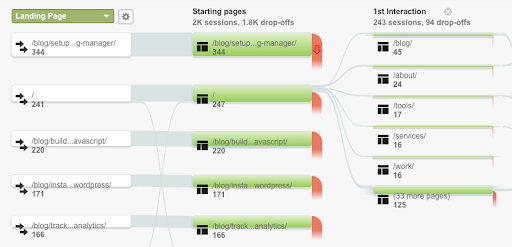

The next step in the architecture planning process will be an analysis of the user behaviour on the site, as well as the site’s performance in comparison to other channels. Here there are a number of data touch points you can use to inform your analysis:

- Multi-channel funnel reports, derived via Google Analytics and the MCF API

- Behavioural analysis in Google Analytics, determining behaviour flow and drop-off points

- Internal site search logs and the pages they occurred on

- Source / Medium reporting, showing traffic origin

These analysis can help identify restructuring opportunities and user search intent pain-points that exist. Use tools such as Slickplan, Lucidchart, or Flowmapp for assistance in visualising, easily restructuring and planning the new sitemap.

Conclusion

Website architecture planning is a process that seeks the optimal structure of links between internal pages in a way that satisfies both the user journey and the search engine crawlers’ understanding of the site.

As such, there is a need for incorporating search intent in the process of planning and link structure. This can not only assist for a pleasant journey throughout the site, based on the visitors’ previous experience with a given topic and their content expectations, but also provide signals to crawlers about the links, authoritativeness, and trustworthiness of the site.