When we talk about the notion of a crawl budget we touch a nerve in the SEO ecosystem. On one hand, there are sceptics who believe that crawl budget is nothing more than a brilliantly marketed definition, and on the other hand, we have defenders of a technique used by Google to prioritize the exploration of the pages of a website.

According to Google, the crawl budget is a concept that has been misnamed by SEO professionnels and there should not be any reason to worry about it for websites with less than 1 million pages. We could, however, call it “crawl ressources” to get closer to the terms laid out in the patents.

In short, the crawl budget – whatever its name – is an additional indicator in the debate, bitterly discussed, but never formally proven.

In spite of that, there are two indicators cited by Google, even though we hear less about them:

- The crawl rate limit, which allows Google to define the ideal crawl speed without negatively impacting the website’s global performances.

- The crawl demand, which allows the number of crawled pages to be increased on a case-by-case basis: a redesign, a set of redirections…

There is one thing, however, that everyone agrees on: logs lines don’t lie. To quote John Mueller: “Log files are so underrated”.

What is a crawl budget reserve?

We define the crawl budget as a unit of time within which Google establishes the URLs to explore according to a rating of their importance. A fortiori, we frequently concede that the crawl budget of a given website should be optimized, ensuring that more pages are being explored by Google at a given time T.

This is where the crawl budget reserve comes in. This concept allows us to identify Google’s current useless explorations in order to transfer this exploration capacity to other pages.

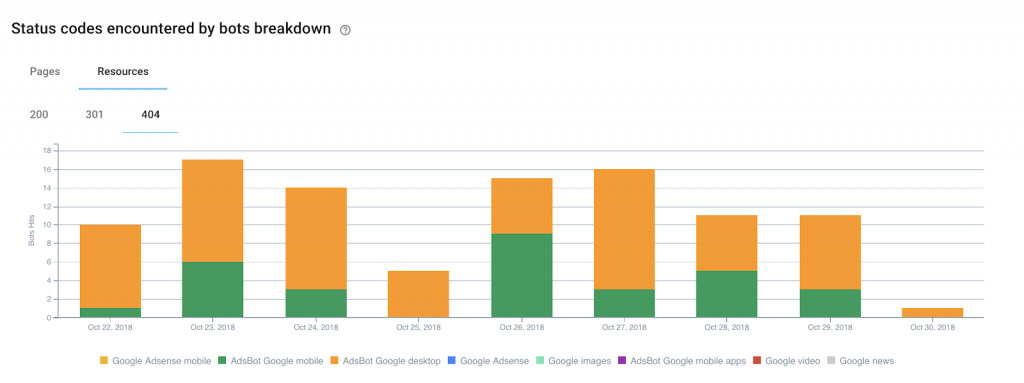

“4xx” errors, both on the pages and resources, naturally come to mind. We can quickly see that Google wastes its time on pages which no longer have a reason to exist. This is a first reserve to work on: redirect hits to facilitate Google’s exploration of pages with real added value.

And the same theory can apply to explorations made by non-SEO User Agents:

We can also make intelligent use of the customized segmentations created with Oncrawl in order to identify the URLs which don’t need attention from Google. These URLs can be spotted using various strategies: tags used to classify editorial content but which have no value as a web page, pages related to the purchase process…

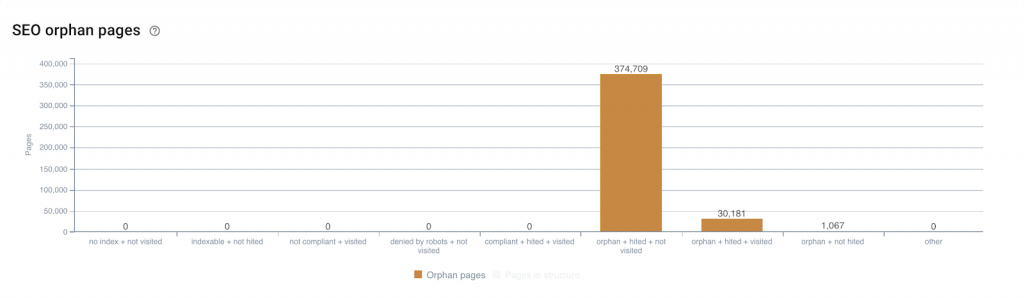

We also know that when the crawl perimeter is not reached, Google may end up crawling URLs which do not have — or no longer have — added value and have consequently been removed from the website’s structure: orphan pages.

Some of these pages may continue to receive hits from Google. When this is the case and when these pages no longer receive organic visits, they should also be among the first pages handled in order to reallocate their reserve of hits to other pages.

How to measure the results?

Our field is not an exact science. The main question when we mention taking advantage of crawl budget reserves is: “How can I tell, once I have put optimizations in place, if Google has taken an interest by my other pages?”

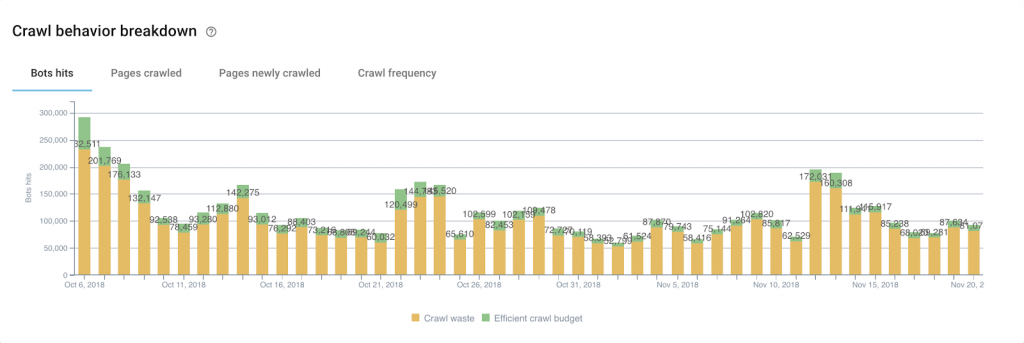

First, we can easily see whether the optimizations carried out for a group of pages produce the expected behavior from Google.

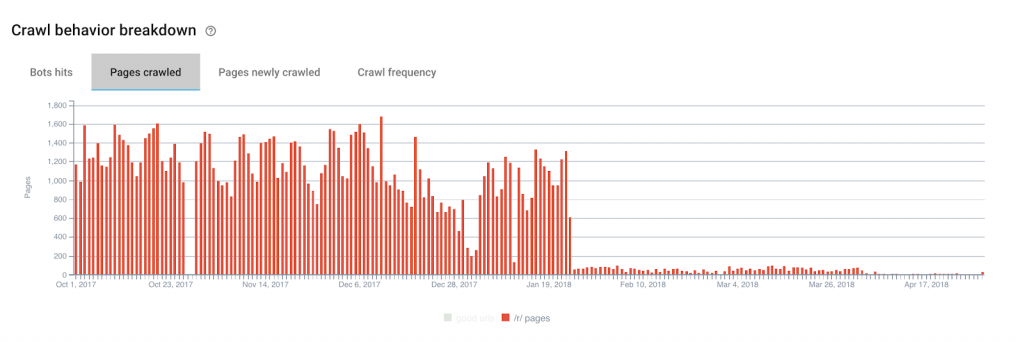

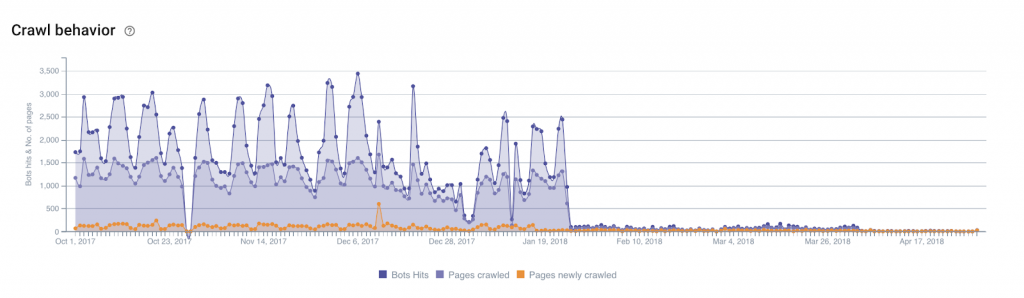

The illustration here is all but screaming its proof: despite a bit of residue after 19 January 2018, we can clearly see that Google’s crawl of our useless pages is close to zero.

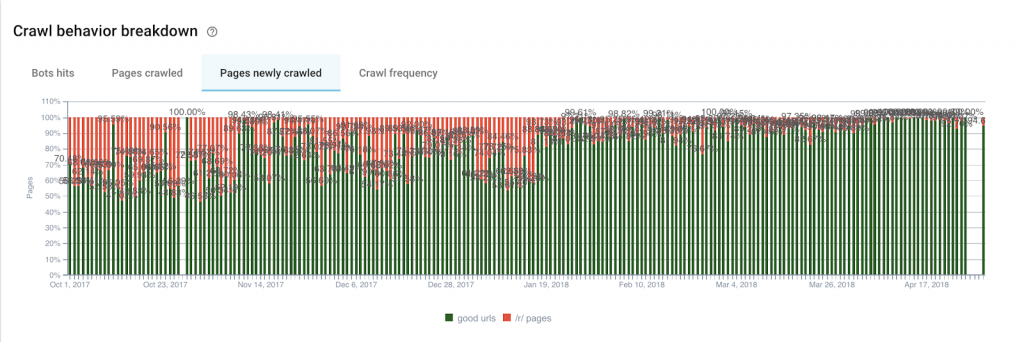

If we now turn to newly crawled pages, we can see that for our “efficient crawl budget” group, we have moved from an average of 58% of the newly crawled pages per day to 88%.

By applying the Base filter to our group of pages to remove, we can also clearly see the result:

Today, it is difficult, if not impossible, to precisely identify a crawl schema: that is, to define a point of entry and follow, URL by URL, Google’s path for a particular group of pages. Probably because Google doesn’t behave like this and, further, its behavior likely isn’t logical. Identifying of benefits after taking advantage of crawl budget reserves remains imprecise because we can’t quantify all of the related circumstances. However, in light of the illustrations and metrics discussed above, we do observe a global modification of Google’s behavior between pages optimized for an efficient crawl budget and those with a inefficient use of crawl budget.